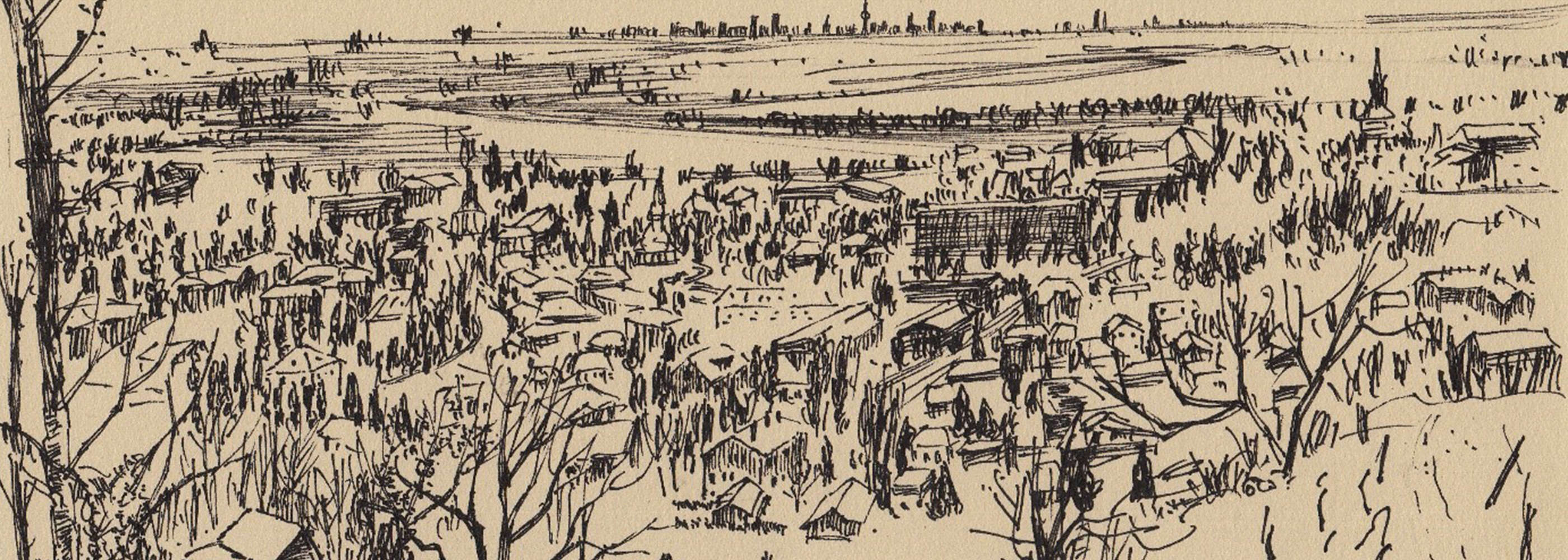

Drawing: Meng Huang

Christmas 2020, Berlin had never looked like this before: the lonely Christmas lights, the few open Turkish snack bars, the occasional sirens piercing the emptiness, the passing police and ambulance vehicles in a hurry, the pedestrians walking with a sense of urgency, the silence and emptiness of the streets. Since autumn and winter, following the initial "hard lockdown," the number of infections and deaths from the virus suddenly surged, and the hospitals were desperate. However, some believe it's a lie by the government and the pharmaceutical industry. There are still people marching in the streets and even storming the Berlin Capitol to protest against the government's quarantine measures. The second "hard lockdown," ordered in November, was the high price paid in the land of freedom, I think.

A year ago, I fled from another capital that had been eerily locked down and returned to Berlin, where life was still ongoing. Soon after, the pandemic began to spread here, theaters and cinemas were closed, and all gatherings were canceled, a harsh punishment for a city known for its culture. I spent nearly a year in Berlin this time, my longest stay yet, and since March, I could only communicate with my friends who lived in the same city through phone calls. Every week, I would ride the nearly deserted subway to the eastern part of Kreuzberg to participate in a rehearsal about Earth, the solar system, galaxy, and the universe. We gathered on the lawn, overshadowed by the pandemic and gravity, while our thoughts soared to Mars and Pluto, wandering through the universe or venting. We come from different cultures, and in Berlin, every immigrant who has settled here calls themselves a Berliner. Here, I have learned that a city can harbor very diverse ethnic groups, languages, and cultures that overlap and peacefully coexist, forming the lifeblood of the city.

From my first visit to East Berlin in 1988 until today, I have witnessed Berlin's transformation from an isolated island into a world of dreamers (both mentally and materially, as Berlin is not immune, and it has become a place where real estate developers have made their fortunes). Every profound encounter I had in Berlin was an encounter with theater, and through that, I formed friendships with certain people. Sometimes, the fire within me, which had been rendered powerless by confusion, was reignited here through an exceptional performance and the ensuing lively discussion, or through a person and their strength.

Berlin has an inexhaustible supply of new things waiting for a visitor, and even though I have left the city several times, each time I return, I feel like I have arrived in a new yet familiar city, rediscovering a lake and a forest, a forgotten memory and an unexpected encounter, a railway line leading away in the evening twilight. Berlin has allowed me to understand what a city truly is.

The first time I traveled to Berlin was in the winter of 1991, shortly after I had come to the University of Bern in Switzerland as a theater student when the faculty organized a trip to the Berlin Theater Festival, a place that theater dreamers in the 1990s had to pilgrimage to. The weather, the streets, the buildings, it was cold, dilapidated, and run-down, with a lot of graffiti on the houses and the old subway that ran through the city, except for the classical reliefs and wide door openings that reminded us of the city's former golden era. We went to the square named after the revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, where the Volksbühne of East Berlin was located. We walked through the district known as Little Istanbul, where laundry dried in the windows, old people sat on the street and drank tea, and children played, a completely different scene from the rest of the city that I was familiar with. When I arrived at the People's Theater, it was already full of people, and the building had the character of the pre-socialist era, where that evening the award-winning play "Clouds, Home" by the groundbreaking Austrian playwright Elfriede Jelinek was performed.

It was only two years after the German reunification when the socialist bloc began to crumble, and the enthusiasm waned as numerous East German companies closed, and the newly freed East Germans lost their jobs in droves. At that time, Frank Castorf, the former East German director, was on the verge of becoming the artistic director of the Volksbühne. His appointment was met with controversy and even insults from the West German theater community because Castorf's provocative rhetoric and texts confronted societal reality and mercilessly exposed the arrogant and narrow-minded politicians and cultural creators of Western society who saw themselves as victors. During his 25-year tenure, the People's Theater worked tirelessly for the people, offering much lower ticket prices than other theaters in Berlin.

The performance that winter was packed and hot, and unlike my previous theater experiences, it was not filled with elegantly dressed, uptight middle-class people I lived with in Zurich at the time, but with an eclectic Berlin audience, young women with shaved heads, boys with earrings. The word "punk" became familiar to me then; everyone seemed full of personality and energy. The audience remained silent during the performance, and after it ended, there was endless applause and cheering, and many people gathered on the lawn for a long time to drink and chat. It was an atmosphere that I have experienced countless times in Berlin since then. When Castorf stepped down from office in 2017, the Volksbühne became the liveliest and most avant-garde city theater in Berlin and even in the German-speaking world, funded by the government.

It was also in this gray Berlin when a friend took me to an exhibition where I got to know Qin Yufen and Zhu Jinshi, the first Chinese artists to come to Europe after the country's opening up. Back then, they lived on the outskirts of the city, and after a ride, you had to walk through a forest to reach their house, as if it were a hidden place of tranquility. They were surrounded by poets, artists, and explorers in search of adventure. At that time, it seemed that only Berlin could bring together such an interesting group of people, all of whom were poor and happy. Making dumplings with Xiaoqin (Little Qin) and Jinshi was a rare feast for all of us foreigners. I remember entering their camp-like studio and house, where their abstract paintings adorned the walls and were neatly stacked with everyday items like soy sauce bottles, drying racks, and bamboo, of which Xiao Qin said they were the material for her installations. Back then, I couldn't imagine how these objects could transform into works of art. After they moved, I visited them every time I was in Berlin, and each time, I happened to meet new people, like the actor Feng Yuanzheng from Beijing People's Art Theatre and the filmmakers Ma Yingli and Li Yang, all of whom I got to know in Berlin.

It was in 2004 that I got to know Berlin better. At that time, I had moved to Beijing and came to Berlin with director Lin Zhaohua from Beijing People's Art Theatre to watch performances, meet theater colleagues, discuss collaborations, and reunite with my long-time friends, Xiao Qin and Jin Shi. In the spring of 2004, we jointly organized a week of contemporary German theater with the Goethe-Institut in Beijing at the People's Art Theatre, which prompted director Lin to come to Berlin himself, with me organizing, accompanying, and translating throughout the entire trip. On the day we arrived in Berlin, we headed to the Volksbühne, and Xiao Qin joined us to watch a six-hour performance directed by Castorf based on Dostoevsky's novel "The Idiot." This adaptation was a groundbreaking work by Castorf, where a city was built into the entire theater space, and the audience sat on a stage constructed on three levels as part of the city. During the performance, the audience was rotated into specific positions by a turntable, and many of the actors' scenes were only visible through multiple video monitors of various sizes hanging above, so as a viewer, you could only see a part of it at a time, which corresponded to our perception of the real world and truth. I translated as much as I could for director Lin, but I still missed a lot. During the intermission, I could barely stand on my feet, and director Lin was so tired that I advised him to go back to the hotel, but he insisted on staying until the end. Afterwards, director Lin told me that the atmosphere in the theater was so contagious that he couldn't go to bed. For decades, director Lin had wandered between state theater and personal dreams. In his later years, he hoped to break through the rules and boundaries of the theater landscape more thoroughly and collide various avant-garde ideas with the reality of the country. In 2004, at the age of almost 70, he and I traveled to several major theaters in Berlin in 10 days, met with the artistic directors during the day to discuss collaborations, and watched performances until late at night. Director Lin had the vision to change the state of Chinese theater, and he was happy and passionate about it.

I fast forward to an evening in 2017 when I managed to get a ticket for Castorf's final production of "Faust" at the Volksbühne, one of the top 10 productions selected for the Berliner Theatertreffen in 2018. The director expanded the form and content of the second part of "Faust" significantly, incorporating a vast array of symbols and scenes from the colonial, pre-socialist, and globalization eras, all revolving on a turntable. The cast consisted almost entirely of the actors who had been with the Volksbühne for 25 years. The performance lasted nearly seven hours, with two intermissions, and the theater was completely stripped of seating; all the audience sat on the floor as if on a steep hill, and the theater was full until after 1 a.m. At the end of the performance, when the actors onscreen brought out director Castorf, the enthusiastic audience stood up and gave more than 40 minutes of applause in farewell. I stood in the crowd and couldn't hold back my tears; I couldn't tell whether it was emotion, sadness, or loss—it was all of it. In that moment, the evening when I was with director Lin at the Volksbühne flashed before my eyes and merged with the present moment. Yes, do we still have the passion and ideals we once had? What have we changed? Or have we been changed?

Here's a brief introduction to the Berliner Theatertreffen, a unique spectacle in a European metropolis. The festival has been held annually since the 1960s and has now been running for 56 years. Every year, theater critics select the top ten premieres from the German-speaking world from the previous year and invite them to Berlin. In 2020, due to the pandemic, some of the festival's productions were only available online, which spread among theater enthusiasts around the world, but it was not the same as seeing them live. Berlin's theater culture dates back to the 1950s when Brecht and Weigel founded the theater in East Berlin. Brecht's theater was the political stage for bold social reforms, aiming to shake up every citizen to engage in discussion, participation, and changing the system and the environment in which they lived through this stage.

In the 1960s, the Berlin Wall divided Germany and split theater aesthetics on both sides. When the Wall fell in the 1990s, and West German theater was still detaching itself from the psychological realism of the past and turning towards abstract aesthetics, East German playwrights and directors re-emerged with a completely different style that reflected their own history, exposed the post-reunification system, and dealt with the social issues of the time. East German playwright Heiner Müller, who became the artistic director of the Berliner Ensemble under Brecht in the 1990s, further developed Brecht's theatrical vision, and his postmodern plays and Castorf's directorial style had a profound influence on theater-makers and audiences who grew up after German reunification. They deconstructed classics, collaged texts, abandoned empathetic role-playing and representation, considered space, music, and video as their own narrative languages. Their work is direct, violent, desperate, and dark.

Since the turn of the century, Berlin has given rise to three distinctive European art collectives: Rimini Protokoll, Gob Squad, and She She Pop. Over the past decade, they have pushed boundaries by combining modern technology, documentary material, the environment, pop culture, and theater, making Berlin their creative home. They have been invited to the Berliner Theaterfestival almost every year and have traveled the world experimenting with their creative ideas. Compared to other European cities, Berlin remains a place where the seeds of experimentation flourish, thanks to its open-minded Berliners, affordable prices, and strong state support for theater culture. The Berliner Theaterfestival has become an event for theater enthusiasts from around the world.

In 2015, when I was already living in Berlin, a very significant event took place at my home: the interactive performance "Home Visit Europe." In May of the same year, Rimini Protokoll launched the "Home Visit Europe" project with 60 performances, each lasting an hour and a half, in private apartments. In the first round, 60 apartments in different districts of Berlin were booked for three or four performances each evening, with a total of 15 participants, including the host of the apartment, meaning that every person who bought a ticket and attended was a participant. The work broke with the conventional concept of theater, completely blurring the line between performers and the audience. It considered every microcosm, i.e., the home, as a public platform for exploring European history, culture, change, and the current state of the European community, with each individual as a protagonist in the community. One of the 60 performances took place at my home, which I had just moved into.

The living room was equipped with a large table for 15 people, which could consist of two or three tables, and a hand-painted map of Europe that served as a tablecloth, along with a small manual device that looked like an old-fashioned printed ticket, and some colorful markers. Each person who entered took a seat, one after the other, with a cup of coffee or tea, and started drawing on the map to indicate where they were from and in which cities they had lived. Then, one of the Rimini Protokoll team briefly explained the rules, and the performance began.

Starting with me as the host, I turned the small device, which would dispense a slip of paper that had to be torn off to perform a task, play a game, or answer a question described on the paper, and then passed it on. Each person participated in different ways, from drawing, narrating, and reenacting actions to raising their hand and performing an everyday task, and concluding with a quiz where two-person teams answered multiple-choice questions on a mobile app developed by Rimini Protokoll. The "home visit" began with the host's house and its surroundings, expanding into questions about who the person is, where they come from, when the European community emerged, and moved on to political questions, such as whether Greece should be excluded from the European community due to the debt crisis. Towards the end of the performance, one of the participants, according to a slip of paper, took a cake out of the oven. The cake was distributed according to the number of points each group earned for answering the quiz questions. This everyday action turned into a political twist: did the size of the cake to be distributed depend on whether one won or lost? The evening ended with a mix of light-hearted games and serious discussions, and the participants were so enthusiastic that I invited them to have wine to continue the conversation. One can imagine how many nights in Berlin, when 60 private apartments were transformed into public spaces and 900 people from diverse cultural backgrounds came closer to each other through a serious game.

The only live performance I saw in 2020 was the 7.5-hour marathon solo performance called "Name Her," performed by the performance artist Anne Tismer at the small Berlin theater Ballhaus Ost. It absolutely blew me away! If theater is the link between Berlin and me, then Anne is the one who continues to make me love theater. Her performance was divided into four parts, each lasting one and a half hours, and Anne performed alone from 6:00 pm to 1:30 am after midnight. What power and spirit! She gathered thousands of forgotten, neglected, or otherwise overshadowed female mathematicians, astronomers, composers, artists, leaders of political movements, etc., from all over the world, from ancient times to the present. For this performance, Anne could only choose 200 of them. She brought them to life with vivid storytelling, captivating dance, and tremendous endurance, along with background information from a triptych video as a stage setting. Anne bridged a gap in human history and allowed these women to shine once again many years later. Anne told me that the list was still long, and she regretted that she could only introduce so many. Due to the pandemic, only 20 spectators were allowed in the theater, but "Name Her" was the best theater experience for me in 2020, perhaps even in a long time.

It was also the year when Anne began bringing together artists from Africa, Korea, Sweden, and elsewhere to look beyond Earth to the planets of the solar system, the galaxy, the dark matter, and dark energy of the universe. Anne was once a sought-after star in the famous theaters of the German-speaking world. Due to her strong dissatisfaction with the theater system, which was still dominated by men, she left the system and became independent, which was financially much more challenging than before. But Anne said she became happier. She spends the rest of her time taking courses in mathematics and physics and plans to return to university to study physics. I admire Anne's drive, and through collaboration with her and a small glimpse into the vastness of the world, it becomes increasingly clear how small this place where we live is. The performance was postponed multiple times due to the pandemic, and I told Anne that even if it were delayed by 10 years, it would be nothing compared to the universe, which is measured in millions of light-years. Anne said that as long as we are still here, we will dance together until the day of the premiere.

In "Name Her," Anne mentioned a number of female artists by name. One of them was my friend Qin Yufen, whom Anne became aware of through her installation at the Berlin gallery Schwartzsche Villa. Over the years, like Xiao Qin, I have traveled back and forth between Berlin and Beijing, and perhaps due to our similar life circumstances, I found it surprising how seemingly ordinary materials in different spaces transformed into installations that moved me deeply. In the classical, church-like hall, hundreds of white clotheslines were spread out in an octagonal formation, with rice papers hanging from them, and small black speakers were placed in between. The digital sound effects from Xiao Qin's manipulation of the Peking opera "Yutangchun" mixed with the pure white of silence, as if many women from the distant past had come to tell their stories. On the pond in front of the House of World Cultures, clotheslines in various colors (there they are again, but with a completely different image and metaphor) were staggered, and when viewed from afar, the slender structures floated in front of the heavy building, creating a mobile "city in the wind" before our eyes. I recall that Xiao Qin had already worked with disposable masks in the mid-1990s. At that time, she had draped three thousand white masks with white cotton threads from the ceiling, forming a massive formation in the air, and from a distance, they looked like flying birds reminiscent of a bird migration at dawn. The work was titled "Light Boats."

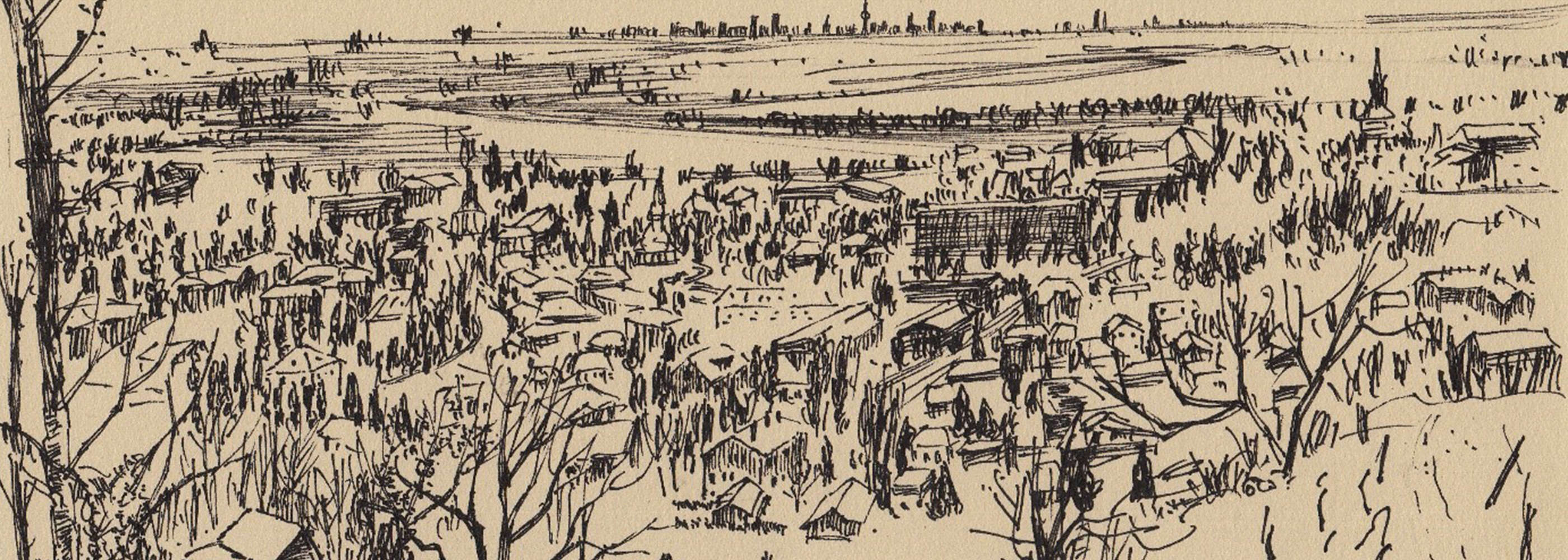

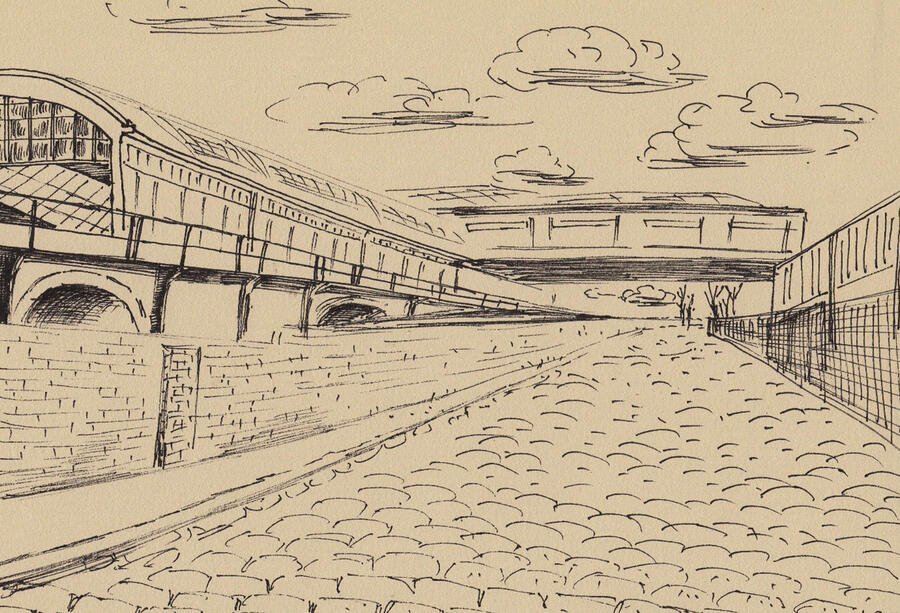

Drawing: Meng Huang

During the pandemic, Anna and I visited the solo exhibition of the artist Meng Huang in a Berlin gallery, followed by a visit to his studio in the northeast, where I saw the original series "Far Away." I had seen this series in a catalog a few years ago, in black and white and shades of gray. I was fascinated by the atmosphere of the paintings and felt that one had to see the originals, much like going to the theater to experience a performance. I gazed longingly at an almost six-square-meter painting, surrounded by trees of varying heights, with snow still clinging to their branches and leaves. A solitary telephone pole stood on the nearby right side, with another further away. In the center of the painting, a railroad track extended straight and unyielding into the distance, merging with the cloud-covered sky. Weeds stubbornly sprouted from the gravel between the track's sleepers. The painting seemed to resonate with Berlin at that time, as well as with my own experiences. Berlin began the year 2021 with a drizzle of snow and rain, and the "hard lockdown" extended until mid-February. No one knew how long the pandemic would hold us in its grip or when we could travel afar again.

Berlin still offers an inexhaustible treasure trove of new discoveries for someone who has already arrived. It allows for the rediscovery of an untold narrative. A city in the wind and a morning hike. A railroad track in the clouds leading to a distant land. And the opportunity to continue wandering or running through a universe measured in light-years. A writer once summarized cities as follows: cities that have endured through time and continue to be guided by their desires; cities that are either extinguished by their desires or extinguish those desires themselves. Through Berlin, I have come to understand what makes a city.